Guide to the Classics: Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’

- Oct 4, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 25, 2023

Abandon all hope, ye who enter here!

So warns the inscription on the gates of the inferno, the first realm of Dante Alighieri’s celebrated work, now known as the “Divine Comedy.” “La Commedia,” as Dante originally named it, is an imaginary journey through the three realms of the afterlife: inferno (hell), purgatorio (purgatory), and paradiso (heaven).

It might not sound all that funny, but Dante called his epic poem a comedy because, unlike tragedies that begin on a high note and end tragically, comedies begin badly but end well. The poem indeed ends well, with the protagonist, also named Dante, reaching his desired destination—heaven—a place of beauty and calm, light, and ultimate good. Conversely, the inferno is dark, morose, and inhabited by irredeemable sinners.

Dante wrote the comedy during his exile from Florence between 1302 and his death in 1321. It is the first significant text written in the Italian vernacular and is written in terza rima, an interlocking three-line rhyme scheme invented by the author.

Dante set the beginning of the story on Holy Thursday, 1300, when he was 35 years old. He alludes to being “middle aged” in the opening lines of the poem:

Halfway through our life’s journey I woke to find myself within a dark wood because I had strayed from the correct path. Oh how hard it is to describe how harsh and tough that savage wood was The very thought of it renews the fear!

To Hell, and Back Again

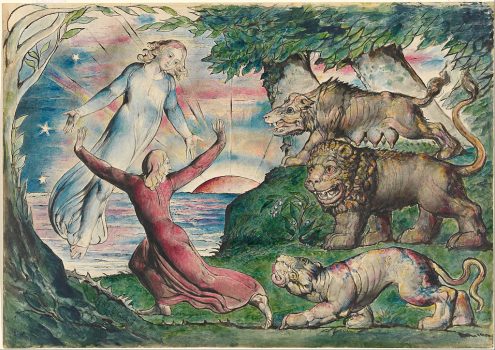

At the beginning of “Inferno,” Dante alludes to the apocalyptic vision of the biblical Book of Revelation. In a dark wood, three menacing beasts, a leopard, a lion, and a she-wolf—respectively symbolizing lust, pride, and greed—prevent Dante from climbing a mountain.

As Dante despairs, the Roman poet Virgil, author of the “Aeneid,” appears, announcing that he has been sent to guide him. They must first descend into hell, a cone-shaped crater that was caused by the fall of Lucifer.

Before beginning the journey, and in keeping with the classical epic tradition, Dante invokes the goddesses known as muses to inspire him, something he will do at the beginning of the next two books, “Purgatorio” and “Paradiso.”

Dante and Virgil must pass through nine circles of hell, in which the punishments increase in severity to match the gravity of the vices being punished. In the first circle are mythological and historical characters who died before Christianity was founded and were therefore not initiated through baptism. Lingering here are noble and virtuous characters, like Plato, Aristotle, Galen, Avicenna, Cicero, and Ovid.

In the second circle, Dante is distraught by the cruelty of the punishment he observes. There, he encounters the souls of the lustful, including the legendary Tristan and Isolde and the historical Francesca da Rimini and her lover Paolo. Murdered by Francesca’s husband and Paolo’s brother, Giovanni Malatesta, these two souls drift aimlessly, their bodies fused together as punishment for adultery. They are joined for eternity, inverting the biblical prescription in Matthew that “what God has joined together, let man not separate.”

In the remaining seven circles of hell, Dante and Virgil observe punishments that are so grisly that sinners are reduced to grotesque conditions. These inspired the frescoes depicting the final judgment day that the painter Giotto painted around the walls and ceiling of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua.

The writer Dante’s friend and compatriot, Giotto was commissioned to paint the inside of the chapel by the son of an infamous usurer that Dante identifies in the seventh circle of hell. There, men with moneybags hanging round their necks flick off flames, just as dogs shoo away insects in summer.

In the next, the circle of the fraudulent, Dante and Virgil encounter popes guilty of simony (or the selling of church services). Having inverted the moral order, they face an eternity buried upside down with their heads in the trenches. Only their legs can be seen from above, waving around frantically.

In the ninth circle, the pilgrims see the Count Ugolino chomping on the skull of Archbishop Ruggieri, the punishment for treachery. In reality Ugolino conspired against his party, the Ghibellines, to bring the opposing Guelfs to power. The archbishop later betrayed and imprisoned Ugolino with his offspring, gradually starving them to death.

Finally the pilgrims arrive at the center of the earth, where they must scale the hairy sides of Lucifer to be able to ascend to the surface of the earth to get to purgatory, where they must be cleaned of the stain of hell. At the entrance of purgatory, an angel inscribes the letter “P” on Dante’s forehead seven times with the tip of his sword, saying, “Make sure you cleanse these wounds when you are inside.” Each “P” stands for piaghe (wounds) that form from peccati (sins). Dante must work off and cleanse away each of them in the seven terraces of purgatory. As he leaves each terrace repented, the angel brushes his forehead, removing one of the letters.

Renewed and purified, Dante is now disposed to rise to “the stars.” Drawing on the writings of Saint Augustine, a woman called Beatrice, who has taken over from Virgil and guides Dante through heaven, explains that God’s creations, exiled to earth, long to return to their place of origin. Dante and Beatrice ascend through several heavens, the moon, and the planets, to the Empyrean, the heaven of divine peace. Like “Inferno” and “Purgatorio,” “Paradiso” ends with a reference to the stars:

Here high fantasy lost its impulse but my will and desire were already propelled, as a wheel is equally moved by the love that moves the sun and other stars.

Dante Through the Ages

Early commentators focused on interpreting the work as an allegory for the life of Jesus. In his “Life of Dante,” Giovanni Boccaccio, author of the “Decameron,” classified Dante as a prophet and his poem a prophecy. Humanist Cristoforo Landino (1424–98) viewed the poem as a metaphor for the soul’s journey back to God, and Neapolitan political philosopher Giambattista Vico (1668–1744) saw the “Divine Comedy” as a product of its barbarous time and Dante as the historian of his age, labeling him the Tuscan Homer.

More recently, the “Divine Comedy” has inspired many creative works including art, architecture, literature, music, radio, film, television, comics, animations, digital arts, computer games, and even a papal encyclical, “Deus caritas est” (2006), which, according to Pope Benedict XVI was inspired by the final verse of “Paradiso.”

It is most often Dante’s “Inferno,” its graphic imagery and twisted characters, that has inspired littérateurs like Chaucer, Milton, Honoré de Balzac, Marx, Elliot, Forster, Beckett, Primo Levi, and Borges.

Few films have incorporated the entire epic tale. The earliest silent films, in 1911 (“L’Inferno”) and 1924 (“Dante’s Inferno”), and the first motion picture in 1935 (also “Dante’s Inferno”) all focused on the creatures and events of the inferno.

Peter Greenaway and Tom Phillips’s multi-award winning 1990 “A TV Dante” juxtaposes narration by John Gielgud, electronic images and sounds, with asides by experts, such as explanations of the three “beasts” by David Attenborough. A 2010 animation and 2012 documentary focus on the horror of the inferno, while another terrifying 2010 animation is based on a video game and departs considerably from the original.

Nor must the inferno be the focus to instill fear or terror. The film “American Psycho” is among 33 films with no connection to the “Divine Comedy” that contain, collectively, 64 occurrences of the iconic phrase at the gates of the inferno: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here,” a phrase that still inspires dread and terror in the audience almost 700 years later.

Frances Di Lauro is a senior lecturer and chair of the department of writing studies at the University of Sydney in Australia. This article originally was originally published on The Conversation.

Contributed by Frances Di Lauro