In the Light of Italy, Artists Paint ‘True to Nature’

- Mar 20, 2020

- 7 min read

Washington's National Gallery of Art presents oil sketches from across Europe

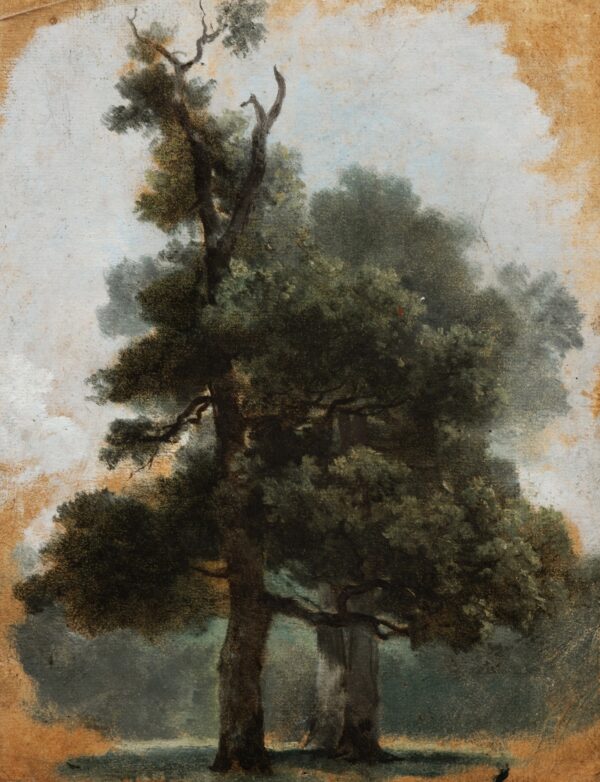

“No two days are alike, nor even two hours; neither were there ever two leaves of a tree alike since the creation of all the world; and the genuine productions of art, like those of nature, are all distinct from each other,” British landscape painter John Constable said.

Constable referred to nature’s only constant: change. An academic art studio can never simulate the way the light falls on the land at a particular time of day. Artists needed to go out and study nature for themselves.

“In the late 18th century and across the 19th century, you simply were not an educated artist until you went to Rome and were steeped in ancient culture, ancient architecture, ancient sculpture, Renaissance and Baroque painting and architecture—and increasingly, in the 1780s, and 1790s, going out into the Roman campagna [countryside] and recording the beautiful, magical light of Italy; the topography of the Roman campagna.” Mary Morton said. Morton is the curator and head of the department of French paintings at Washington’s National Gallery of Art.

French landscape artist Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes further encouraged young artists to paint oils sketches outdoors with his influential treatise on landscape painting, published in 1800.

Young artists traveled from European capitals such as Paris, Copenhagen, and Berlin to complete their art education by sketching the Roman countryside in oils: a tradition called plein-air painting (open-air painting.) These European artists’ plein-air paintings immortalized the Italian landscape, and in turn, Italy—true to its nature as a country steeped in ancient artistic traditions—trained some of Europe’s greatest artists outdoors.

The artists vigorously painted the mountains, valleys, rivers, waterfalls, and even erupting volcanoes—quickly making note of every little thing between the earth and the sky. These oil sketches were not intended as detailed finished paintings but as studies or, as Morton describes them, field notes.

Artists would circulate these sketches among one another, or archive the paintings in their studios. In the studio, artists would develop some of the oil sketches into finished works, or they’d return to the same site several times in order to make a more finished work, Morton explained via email. When these artists returned to their home countries, they referenced the oil sketches for fresh compositions, and they also continued the tradition of making open-air oil sketches focusing on their native landscapes.

Visitors can see Europe’s landscapes unfold through about 100 oil sketches in the exhibition “True to Nature: Open-Air Painting in Europe, 1780–1870,” at the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington.

The exhibits are from the NGA’s collection and two European collections: the Foundation Custodia, Frits Lugt Collection in Paris and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, UK. Morton curated the exhibition together with Foundation Custodia director Ger Luijten and the Fitzwilliam Museum’s keeper of paintings, drawings, and prints, Jane Munro.

The exhibition is a discovery of many things: outdoor oil sketches, lesser-known artists, and the beauty of Europe.

Rediscovering Plein-Air Paintings

Only over the last couple of decades has the tradition of oil sketching become more fully understood, Morton said. The curatorial team researched 17th- and 18th-century scholarship for the exhibition and also the work of the late Philip Conisbee who, from 1993 to 2008, was the NGA’s senior European paintings curator.

All this history is discussed in the comprehensive exhibition catalog “True to Nature: Open-Air Painting in Europe, 1780–1870.” In 1954, John Gere, a curator in the department of prints and drawings at the British Museum and specialist in old master Italian drawings, spotted some plein-air paintings at auction. This piqued Gere’s interest in the genre, and along with his wife, he started collecting these sketches, sparking a rediscovery of plein-air painting. Conisbee saw the collection at the Geres’ home and he began additional research.

In 1980, Conisbee wrote the exhibition catalog entries for the first comprehensive exhibition of plein-air paintings at the Fitzwilliam Museum, according to the exhibition catalog. For the next 40 years, he researched the plein-air tradition and built the NGA’s collection of these works.

In 1996, he curated “In the Light of Italy: Corot and Early Open-Air Painting” at the NGA, the first American exhibition on the subject. “True to Nature” is a continuation of Conisbee’s work, featuring oil sketches he acquired during his time at the NGA, and new scholarship as well. The exhibition aims to increase understanding on this important, yet relatively unstudied, part of European art history.

Insights Into Plein-Air Painting

Some of the little details we discover can make these sketches all the more endearing and perhaps more relatable to our everyday life. For example, some of these works on paper have one edge that’s clearly been cut with a knife. Just as we may sometimes divide and cut a piece of paper to write notes, some of the oil sketches appear to have been cut from the same sheet by the same artist. And we can imagine the artists preparing their materials: cutting the paper by hand, selecting brushes, and carefully packing the paint. Artists used animal bladders to store the paint or mixed a limited color palette to take with them.

Groups of artists ventured out into the countryside together across often treacherous terrain with their easels, paper, and paints in hand. Italian artist Giuseppe de Nittis traveled six hours every day to paint Italy’s most accessible volcano, Mount Vesuvius. He went part of the way on horseback and for the rest he was carried by a guide, explained Jane Munro from the Fitzwilliam Museum. He did, however, change his route after he felt the earth move, signaling a possible volcanic eruption.

Once on site, artists would have painted each sketch for a set amount of time. As part of their academic art training, they would have been familiar with the discipline of timed life drawings. Just as these artists were able to capture a life model’s pose in short, swift gestures with their charcoal or brush, so they applied the same spirit to capture nature’s nuances in oil. Each oil sketch is “like a pantheistic reverie,” Morton said.

Because these artists had formal art training, each sketch is “a piece of nature that’s been formalized aesthetically and made satisfying for them, because for the most part, most of these are for them,” Morton said.

Embracing Plein-Air Painting

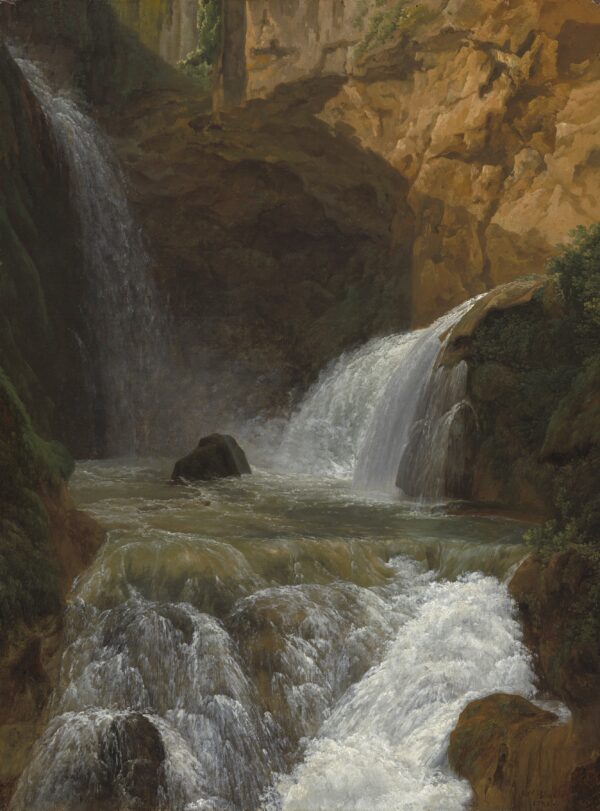

The exhibition starts with two Italian regions, Rome and Naples, and then covers the rest of Europe. Spread over a total of five galleries, the sketches have been grouped by subject matter as the artists would’ve archived them in their own studios: There are rocks and caves, waterfalls, and volcanoes, to name a few of the 11 categories.

Nineteenth-century French landscape painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot was a prolific plein-air painter who brought the tradition to France. As a traditionalist, Corot vowed “to reproduce as scrupulously as possible” what he saw in front of him. Corot’s oil sketch “The Island and Bridge of San Bartolomeo, Rome,” which is featured in the exhibition, attests to this. Corot’s teacher Achille Etna Michallon taught him to paint true to nature, and Michallon must have learned this from his teachers: neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David and Valenciennes.

Valenciennes’s advice to artists was to always start with the sky when painting a vista. Artists could include a band of land as a guide to orientate themselves, but Valenciennes believed the sky set the tonality for the entire landscape, Morton explained.

Valenciennes’s British counterpart, Constable would have agreed. For Constable, the sky was of utmost importance. It’s “the key note, the standard of scale, and the chief organ of sentiment” in a landscape painting, he said.

Constable was obsessed with the sky. He read meteorological reports and would spend hours “skying,”a term he coined for watching and recording the changing skyscape. He annotated his sky studies with weather reports, the direction of light, and more meteorological information. Morton invites us to look at what Constable does with light in his paintings. At the exhibition, we could start with “Cloud Study: Stormy Sunset.”

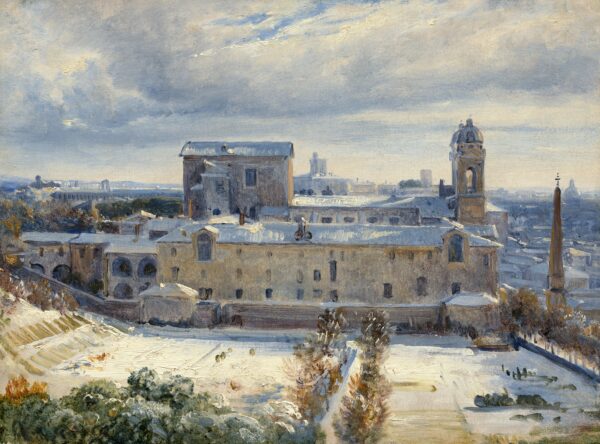

“Santa Trinità dei Monti in the Snow” by André Giroux is painted in a similar palette as Constable’s “Cloud Study: Stormy Sunset.” French students like Giroux, who were sponsored by the French government, stayed at the Villa Medici. Giroux painted the sketch straight from his bedroom window.

In the sketch, a snowy scene unfolds, and in parts Giroux used his finger to paint or scraped through the wet paint. Technical art historian Ann Hoenigswald discovered Giroux’s creative “mark-making” as part of her study of each exhibit to understand more about how these plein-air paintings were rendered.

One of the two female painters featured is Louise-Joséphine Sarazin de Belmont, a student of Valenciennes. Women were not yet permitted to study at art schools, so Valenciennes tutored them. Sarazin de Belmont generally began painting outdoors and then continued working on her paintings to sell on the Parisian art market, Morton said via email. ”Grotto in a Rocky Landscape ” expresses the “thrill of being inside the earth looking out,” Morton said.

Sarazin de Belmont managed to create a huge sense of scale on the paper, which feels as if we are almost popping our head out into the painting’s landscape. She used atmospheric perspective to achieve this: The background fades away while fresh color fills the fore- and middle ground.

French painter Jean-Charles Rémond painted many plein-air oil sketches, but his finished painting “The Eruption of Stromboli, 30 August 1842,” was a commission from the Gallery of Mineralogy and Natural History Museum in Paris. Rich reds and darkness dominate the painting as lava spews from Stromboli.

True to Nature

Jane Munro ponders who is “true to nature”? Are artists like Guiseppe de Nittis, who sketch volcanoes and predict the likelihood of volcanic eruptions by holding their ears to the earth to listen to the lava bubbling below, or are scientists such as physicist Luigi Palmieri, the director of the Vesuvius Observatory, who monitor the earth with their seismographs? We can wonder too.

Morton referred to Baron François Gérard’s rather strongly colored painting full of a purple and red sunset as a wave crashes violently on the rocks. “There’s no way you [can] paint a wave true to nature; you’re going to paint the sensation of a wave, which is what Gérard has done,” she said.

Each of these oil sketches is an artist’s conversation with nature, evoking the sensations and sentiments that were true to that artist at that moment in time.

The exhibition “True to Nature: Open-Air Painting in Europe, 1780–1870” is at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, through May 3, 2020. To find out more, visit NGA.gov

Information in this article is primarily from the audio of the press preview for “True to Nature: Open-Air Painting in Europe, 1780–1870” given by Mary Morton, curator and head of the department of French paintings, at the National Gallery of Art. Jane Munro from the Fitzwilliam Museum also presented.

Contributed by Lorraine Ferrier