The Humble and Noble Nature of Northern Renaissance Art

- Jan 3, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 25, 2023

The Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit connects you with treasures of our past

There’s a prevailing attitude among some art enthusiasts that art that isn’t contemporary isn’t relevant. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has set out to debunk this perspective with an exhibition that runs through June 23, 2019, called “Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance.”

“A lot of people have a sort of hesitancy to engage with 16th-century European art because it just feels so alien to what they are used to now, what they enjoy now, and they shy away from this idea of the princely class spending obscene amounts of money on art objects,” said the exhibition’s curator Elizabeth Cleland by phone.

An example of that enormous expenditure at the exhibition is by Albrecht V, Duke of Bavaria, who annually spent 1,000 years’ worth of soldiers’ wages on art. There’s also the story of Isabella I of Castile—appropriately nicknamed Isabella the Catholic—who was so enamored with devotional tapestries that her art expenditures were competing with the costs of the historic transatlantic exploration by Christopher Columbus.

While many of Isabella’s devotional tapestries were typically small, fit for a door, most 16th-century tapestries covered walls, usually six to eight times the size of the queen’s on view in the show. To tell a full allegorical tale, the collector would often commission five to ten wall-hanging tapestries in one set.

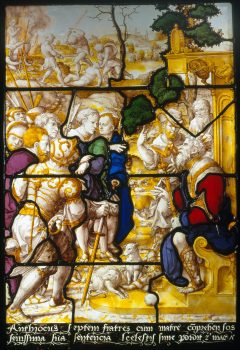

“Saint Veronica,” from the exhibition, illustrates clearly why tapestry-making was so beloved and prestigious. It showcases an artist’s virtuosity, one of the most highly valued characteristics of Renaissance art. It’s like a beautiful painting but made of wool, silk, and gilded silver metal-wrapped threads.

The exhibition isn’t your typical one, however, highlighting only the treasures that royalty could afford. To bring that era’s perception of art a little more down-to-earth, a wide range of Renaissance art is displayed, juxtaposing the most humble, functional pottery with the most exquisite gilded pieces.

To help illustrate the original market value of the art, Cleland calculated the cost of each piece in terms of a stable metric across Europe at the time—one milking cow. So, next to every work, you can see how many milking cows it was worth. “Saint Veronica,” for example, was worth the equivalent of 52 cows, while modest pieces were only fractions of a cow. Tying the art to a real-life metric not only demonstrates the exhibition’s diversity, but also how much art was valued back then.

New Perspectives

For this exhibition, artistic ingenuity wasn’t only reserved for the ancients. Cleland worked with designer Michael Langley, who wanted to transport visitors out of the typical dark, moody lighting of a historical art exhibit so that patrons could see the Renaissance with fresh eyes.

“[We stripped] back the paraphernalia in the gallery to really help people approach these things as if brand new, as if they have just come out of the artists’ workshops, and they’re appearing in their original market for their original consumers,” Cleland said.

With more creative freedom inside the Wrightsman Special Exhibition Gallery, Langley brightened the lighting and displayed works on metal screens, with objects singled out in their own plexiglass boxes.

“That’s one of the joys of working in that temporary gallery, that you can go a little bit outside the box,” Cleland says. “The idea is to try and stop visitors in their tracks … You had this idea of what 16th-century European art was like, but we want you to look at it with new eyes.”

Cleland’s treasure hunt to find the exhibition’s 63 objects was as unique an experience for her as it will likely be for visitors. She’s The Met’s curator for post-medieval European tapestries, one of the most luxurious and regal art forms coming out of that period, so she’s very familiar with the highest-end art. Her expertise reflects what the typical patron is used to seeing at a Renaissance exhibition as well, a gallery’s most valuable, expensive pieces.

For this display, however, Cleland wanted to show how art was appreciated across the entire society during the Northern Renaissance, from the low, middle, and high social classes.

“What I’m hoping to achieve with the installation is to help visitors get a sense of the kaleidoscopic world of Northern Europe in the 16th century. That it’s really exciting,” she said with a contagious zeal.

As Cleland plunged down into The Met’s storeroom with her colleagues—the curators of ceramics and goldsmiths’ works—they discovered art that had never been displayed, typically because it wasn’t at a high enough standard. But these humble treasures, crafted from simple salt-glazed stoneware, not rock crystal and gold, for example, made quite an impact on her.

“Just the nature of working that material, there’s more of an immediacy with the creator,” Cleland said. “You can almost feel the potter working on it, manipulating the material.”

The Bottoms-Up Cup—only worth 1/8th of a cow—is one such work that had been sitting in the storeroom since the 1950s, never having been displayed.

“You’ve got these different effects of the smoothness of the figure’s breastplate, and then these fantastic furry breeches that he’s wearing, and also just the joy of the object itself,” she said. Based on the way it’s displayed, it looks like a figure, but is, in fact, a cup with a handle that rotates 180 degrees so that one can drink out of it.

That charming cup offers insight into that era, connecting us. For one, people throughout society enjoyed art and craftsmanship so much that it was used to enhance functional objects in daily life. Just like the lucky New Yorkers from all walks of life who visit The Met, people of the Renaissance likewise adored art and beauty. It’s also a lighthearted reminder that people of this era appreciated having fun and being merry—no different from us today.

But there are other lessons too, which only arise because of the exhibition’s rainbow of Renaissance art, displaying basic art to the most extraordinary. There are clearly levels to art and craftsmanship. Lower, functional art reflects our basic needs, and connects us to each other, and here to the natural world.

But as you climb the hierarchy of Renaissance art, the artistic themes climb with you, like a ladder to heaven. Maybe that’s why Isabella valued her tapestries’ taking her on a spiritual journey to be as paramount as the journey to the New World.

“We have these very esoteric, religiously potent symbols and this idea that by owning a tapestry representing that subject, you are protected by it,” Cleland says. “It’s a little bit like a pilgrimage.”

J.H. White is an arts, culture, and men’s fashion journalist living in New York.

Contributed by J.H. White

Pure Truth, Kindness and Beauty

"When your heart is unmoved, you will see the truth and reasonable way to face any situation."

Join us on this inspiring journey to visit the artist Loc Duong in Vietnam as he shares his amazing experience while creating “Unmoved.”

His first-ever oil painting makes many people feel at peace and won the Humanity and Culture Award in the last NTD International Figure Painting Competition.