Pedagogist Cassia Harvey: The Classics Are Our Collective Memory, Our Cultural DNA

- Jun 3, 2019

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 20, 2023

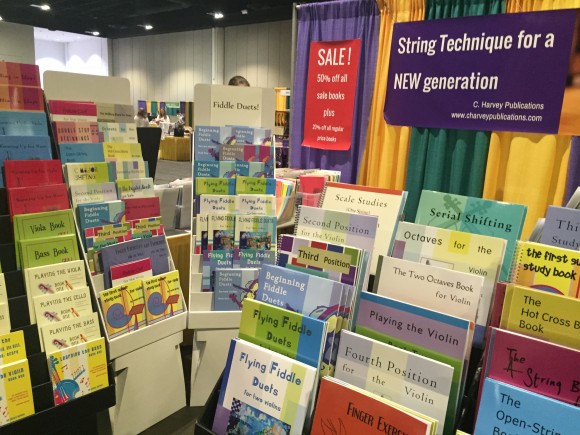

Cassia Harvey has written more than 160 books for cello, viola, and violin. With a methodology that trains players’ hands from the beginning, step by step, to advanced levels, her exercises fill a gap in the pedagogy of stringed instruments.

Becoming “a benchmark household name for string instrumentalists,” according to Philadelphia’s The Key, her company C. Harvey Publications publishes books sold in more than 30 countries around the world.

A composer and cellist, as well as a teacher, Harvey believes the classical arts act as our collective memory—at once allowing us to understand new works, while making further artistic creation possible.

Harvey realized that a complete system of technique could be devised for string players.

From a composer’s perspective, the classics are a reservoir of collective memory to be dipped into and drawn from. Composers go back again and again to the ideas of previous composers, consciously borrowing from or playing with their ideas, Harvey said.

Harvey recently played in a concert featuring a new work, “Masquerade on a Folk Tune” by Ioan Dobrinescu, which starts with a melodic theme, and then, within variations on traditional forms—a folk tune, a bolero, a tango, a Chopin polka—includes atonal moments. Without the traditional musical forms, the atonal moments would likely have puzzled or pushed away the audience.

These variations on a familiar form were more than an homage to the past, Harvey said. They were necessary for the audience members, who could now think, “Ah, I understand.” Our collective, cultural memory offers context for meaning-making—especially in music, in which without familiar patterns, the sounds we hear would sound like gibberish.

Sometimes the collective reservoir brims over and inspiration pours forth, seemingly spontaneously. For 23 years, Harvey had played David Popper’s etudes daily. Of the 40 etudes, she’d play perhaps four a day. Over time, practicing them had become a chore—she felt sick of them and stymied—but she continued to practice them because she could find nothing better.

One day, as though a dam had burst, Harvey started writing exercises to expound on them. She wrote 25 exercises on one etude. Etudes, a bridge between a technical exercise and a fully formed piece, can be beautiful, whereas exercises are purely to train for technique. After years of constant play, her memory of these pieces served as an inexhaustible fountain.

“If I hadn’t written the exercises, then I wouldn’t have seen the ideas behind them.” By writing these exercises, she said, Popper’s etudes “have a new life, which made my practice alive again. When I’m rehearsing, I feel like I’m sitting next to him sometimes.”

Schools of Playing

Exercises for instruments necessarily arise from the traditional repertoire and the patterns within it. An exercise like a scale, for example, is obviously a classical pattern and part of our collective memory.

When it comes to learning methods and exercises for each particular instrument, or for a specific school of playing, it’s best to view it as less like a reservoir and more like a transmitted gene, for classical methods of training are passed down from one generation to the next. They are part of Western music’s cultural DNA.

Each school of training represents a certain way of thinking about how to play. Harvey herself comes from the Italian school of cello playing, which is highly technical. Although her own teacher was not as obsessed with technique as Harvey is, the cultural gene was nonetheless passed on.

Our collective, cultural memory offers context for meaning making.

And each proponent of a school also adds something new to it. Harvey has very flexible but weak hands, so she constantly works to strengthen them. Many of Harvey’s books contain exercises to strengthen the hands. They include, for example, double stops—holding down two notes at once, which requires more force.

“The double stops are foundational, even in exercises that are trying to develop other skills,” she said.

The exercises of Gregor Joseph Werner (1693–1766) focus on speed and agility, abilities which were especially important in his time. Julius Klengel (1859–1933), known for his etudes, his exercises, and his solo cello compositions, “focused on writing pure technique.” His five books, still often used today, contain basic exercises that present cello technique “in a straightforward and clear way,” Harvey said.

Finding Her Path

At age 16, Cassia started teaching the cello. Growing up in a musical family, with her mother and sister both playing violin, it was assumed she would either perform, teach, or do both. She practiced for hours a day, participated in solo competitions, and applied and was accepted into a conservatory.

After acceptance, she took trial lessons with several cellists, but found that no one could help her with a particular technical problem she was having.

Rather than spend tens of thousands of dollars to pursue a formal degree, at 18, Harvey decided to hide away and learn on her own. She bought all of the cello books and method books she could find, but found little on each of the individual positions for the cello.

A position is the placement of the fingers on the cello fingerboard. Like any stringed instrument, the fingering positions create different sounds. But because cello fingerboards have no frets, “the cellist has to develop visual memory of the fingerboard, spatial memory for how far to move, muscle memory for what the arm and hand and fingers do to change positions, and aural memory for how it sounds when the notes are correct in each position,” she said.

As Harvey continued her search, she eventually stumbled onto video footage of Agrippina Vaganova training ballet dancers. The Russian dancer and teacher had formalized a system of ballet instruction that struck a chord with Harvey.

Vaganova had taken apart pieces of classical choreography and simplified each advanced step into the most basic movements. These movements formed the elementary dance exercises of her system. Then, step by step, she made the basic movements more difficult, spreading the training out over eight years to create a complete system.

Harvey realized that a complete system of technique could be devised to incrementally challenge and train the hands of string players, too.

“When students came to me, I was seeing weak hands and fingers, poor knowledge of the fingerboard, and just all-around faulty technique. I wanted to train my hands and my students’ hands to be as capable as the bodies of Vaganova-trained dancers. So I applied the same principles I saw in Vaganova exercises to the exercises I would write.

“Every time I would make a leap in the exercises, a break in the deliberate order of teaching, I would see that students would fail. So I would go back and rewrite sections to make sure everything was taught step by step, with no holes, no breaks, no leaps—no points at which I would leave the student unable to get to the next level,” she said.

And then Harvey’s life took a dramatic turn. One morning when she was walking just a couple of blocks from home, a couple quickly approached her and robbed her at gunpoint. Her bag and everything in it was stolen, including an irreplaceable student’s notebook in which she’d composed exercises, handwritten in pencil.

This was the worst part of the robbery for Harvey: “It did something to me. It made me want to do something so no one could ever take it away from me, take it away from students again,” she said. She realized that her exercises needed to be published.

All through her 20s, Harvey spent her days teaching and most of her nights composing exercises. She’d try them out on herself and on her students. It took her two years just to find her bearings and the patterns necessary for distilling the ideas into exercises. But she completed a whole system of training, which ensured that when students finished a book, they’d be ready to begin the next.

She owes “all of those ideas, that way of thinking, to Vaganova,” she said. Once her books came out, students gave her feedback like “I now understand fourth position.”

Over time, Harvey’s contribution to string pedagogy may too become part of classical music’s cultural DNA.

She’s actually grateful to her robbers in a way, for if she’d remained a performer or a teacher, she said, “I’d be bored, but now I live a varied life, and I’m never bored. It was an amazing gift, a chance to do may different things with the cello.”

In our series “The Classics: Looking Back, Looking Forward,” practitioners involved in the classical arts tell why they think the texts, forms, and methods of the classics are worth keeping and why they continue to look to the past for that which inspires and speaks to us. For the full series, see ept.ms/LookingAtClassics

Contributed by Sharon Kilarski

Pure Truth, Kindness and Beauty

It’s a great pleasure to present to you an inspiring story from the Award-winning painter Lauren Tilden. Her painting “Birds of the Air, Grass of the Field” has won the Bronze Award from the NTD International Figure Painting Competition in 2019.

“Working on that painting was a reminder to me not to worry. There is more to life than the issue you are facing at this moment.” – Lauren said.

While contemplating the value of human life, and how precious it is, the artist’s own young daughter became her stand-in, her persona in the painting. Please join us on this wonderful journey to visit Lauren in West Virginia.